Address

519 St. Lawrence Street

P.O. Box 65

Winchester, Ontario K0C 2K0

P.O. Box 65

Winchester, Ontario K0C 2K0

History

Like many families, the family of Winchester United Church has a long and interesting genealogy. Back in the 1840’s, itinerant ministers from the Methodist Episcopal body (American origin) conducted services in homes, in (present day) Winchester. By 1881, the Methodist Episcopal body began construction of the Sunday School Hall. An act of union, in 1883, joined four branches of the Methodist Church into one body simply called, “The Methodist Church”. This date signifies the formation of our congregation and continues to be the date used for calculating anniversaries. A building committee of John S Ross, Henry Mercill and Aaron Sweet was established to complete the actual church. The congregation decided to worship in the Sunday School Hall until the sanctuary was completed. In 1886 the sanctuary was completed and the church was dedicated on the first Sunday of October.

By an act of Parliament, in 1925, the Methodist, the Congregational and Presbyterian churches were united into the United Church of Canada. At this time, a tablet signifying this union was placed on the exterior wall of the west side of the church.

Over the years, many families have enhanced the interior and exterior of the church by making personal or In Memoriam donations. Examples include:

By an act of Parliament, in 1925, the Methodist, the Congregational and Presbyterian churches were united into the United Church of Canada. At this time, a tablet signifying this union was placed on the exterior wall of the west side of the church.

Over the years, many families have enhanced the interior and exterior of the church by making personal or In Memoriam donations. Examples include:

- the baptismal font in 1924

- the ‘drop’ electric lights in 1926

- the offering plates in 1944

- stained glass windows beginning in 1951

- the Casavant pipe organ in 1960

- the sign in front of the church in 1967

- renovations to the Sunday School Hall 1988-1992

- the baby grand piano in 2008

The Old Limestone Lady of St. Lawrence Street

the story of how a runaway U.S. slave and a pioneer community built a 130-year-old landmark church

By Bert Hill

By Bert Hill

In 1851, a seven-year-old boy watched in shock as his mother Jane and three brothers were sold at a slave auction in Kentucky. If he could understand what was happening, he couldn't do anything about it. He was chained to a post “as if I was a horse” after being sold for $700.

But 30 years later in Winchester, in a testimony to the resilience of the human spirit, Isaac Johnson was hard at work on a new limestone Methodist Church. The skilled stone mason had learned in a harsh world the importance of basic principles, from freedom to construction.

When he discovered that the north wall of the new building was a half-inch out of line, according to a story, he tore down the wall, which had reached the top of the windows. Then he started over again from the six-foot-wide foundation.

Perhaps Johnson or another mason was responsible for a unique feature. Over the windows on the south side are the figures of a sun, half-moon and star clearly visible in stone. The campaign to restore the former Methodist church, now Winchester United Church, has created challenges that some feel are too much to manage. But the history of the 130-year old limestone landmark and its predecessors is a story of struggle, division and tragedies as well as faith and happiness. They make the current campaign to raise $200,000 this year to restore the stately bell tower seem much more manageable.

Johnson carried a terrible truth in his heart as he worked on the church that summer - a project which would ultimately take five years to complete.

But he perfected the skills that would soon lead to a successful career building hospitals, churches, bridges and town halls in Northern New York State and Eastern Ontario. He probably thought often of that day staked to the post under the hot Kentucky sun. When he looked at his mother in the auction ring, “it seemed as if my mother's heart would break”, he recalled in a 1901 memoir. She knew all too well what was happening and who was responsible for the breakup of the family. He pleaded with his new owner to go to his mother. "Come along with me,” he snapped. "I will train you without your mother's help." The final shock was the sale of his youngest brother, two-year-old Eddie, who was taken from his mother when the bids for the two together were too low. He wrote "in a very short time, our happy family was scattered without even the privilege of saying 'Goodbye' to each other, and never again to be seen."He published the memoir "Slavery Days in Old Kentucky" in a bid to find his family. He also wanted to smash the romantic myths about the Confederate South and slavery. "Any system of human slavery is always degrading both to the master and slave."His efforts to find his family failed. But he discovered that the person who had ordered the sale of the family was his father, Richard Yeager, a white tobacco farmer.He had inherited Jane Johnson from his slave-trader father. She was kidnapped in 1840 from Madagascar, an island off the coast of Africa. The couple appeared to live happily as husband and wife raising a family and running the most prosperous farm in the area. But the social pressures from a racist community scandalized by a white man living with a slave woman became unbearable.

He sold the farm and disappeared. The family that was still expecting his return two months later instead was met by a sheriff ordered to sell the family to the highest bidders. Jane Johnson sold for $1,100 while Eddie sold for $200. In total the family went for $3,300.

Isaac was treated harshly by his new owners, working 18-hour days, just two meals a day and frequent whippings. Twice he tried to escape.

One warned Isaac that if he disobeyed, "my duty is to kill you just as I tell you to kill the mule if he doesn't do what is right. There is no more harm in me killing you than than there is in you killing the mule.” The same slave-owner caught his wife teaching slaves lessons from the Bible. “If you teach them to pray and read they may think they are human beings and we will not be able to keep them as slaves.”

The lessons ended and many slaves forgot what they learned “except the Lord's Prayer, so simple and yet so full of meaning and comfort.”

Isaac was forced to watch a fellow slave, Bob, whipped, tortured with hot coals and slowly killed over five days as an example for leading a runaway group. Bob, a formerly free Canadian steamboat engineer kidnapped in New Orleans, had told Isaac of the freedom that beckoned in Canada.

Much later Isaac would meet the sadistic slave-owner - now paralyzed and confined to his bed. "The Lord has answered my prayers and allowed me to see him punished."

As for his father, he was "repulsive" because he could sell his own children and support a system that allowed that to happen.

Isaac finally broke free when the Union Army marched through Kentucky in 1863. When the slave-owner came looking for Isaac, the commanding officer gave his master 15 minutes to clear out. Captain Larkin Smith gave Isaac a job as a cook and revolver and 20 bullets. Isaac relished the first freedoms in his life - to work for pay and to bear a weapon to protect himself. Smith and his regiment returned to their home state of Michigan. From Detroit, Isaac looked across the river to Windsor. “I was going to Canada because then I would be a free man.” But it was 1864 and there was some unfinished business. He enlisted in a new black regiment of the Union Army and was wounded in action in battles in South Carolina.

He lost a finger on his right hand and took three bullets in his left arm which were never removed and caused him trouble as the years advanced.

After the war was over, he spent two years searching for his family in Kentucky. He then worked as a sailor on the Great Lakes and finally stopped at Morrisburg. Later he would recall “I never set my feet upon Canadian soil, even to this day, without a feeling of love and respect for its people of Canada, to me a Canaan.”

He lived in Winchester for about eight years, winning respect for his skills as a stone and lime mason. He married Theodocia Allen on Dec. 28, 1875. She had been born in New York and at 20 was ten years his junior. From pictures it appears she was likely white. On the wedding document for the Morrisburg ceremony, he said he was a "lime mason." Both were Methodists. Gertrude, the first of seven children, was born in Winchester in 1876 and Susan followed five years later. They lived in a log house on the west side of Main Street across from the quarry on a farm that is still in the Baker family. It is about two kilometres south of the church.

Isaac's story was re-issued and updated with an introduction by the St. Lawrence County Historical Association in 1994. Their researchers discovered that Earl Baker, before his death, told researchers that “Mr. Johnson” was remembered in family stories for developing the quarry, building the family home (near a new Anglican Church) and other fine local stone buildings.

The quarry is now full of water and edged by trees. An adjacent property was once a municipal dump.

Isaac also likely worked in lime and quarry operation owned by the Summers family just to the west of the current intersection of County Road 43 and Belanger Road.

The determined young man with a fierce mutton-chop beard and strong eyes stood five feet, eight inches high and his skin was light. One master had derisively described him as a “pumpkin seed nigger from the mountains.” But the new post-war world was booming and opportunities for expert builders were many regardless of race. In the winter months, he worked with wood. He carved a small wood chair for a family friend in 1873. Now in a Waddington museum, it features African patterns and markings.

In 1884, while work continued on the new Winchester Church, he won a contract in Waddington, opposite Morrisburg, for a handsome new town hall and for a stone bridge to the south. He also built a Catholic Church in the area.

He moved to Waddington and later to faster-growing Ogdensburg as new opportunities opened to build a new state mental hospital.

He continued to work on both sides of the border. In 1897 he was injured in a fall from a derrick at a Cornwall quarry. The serious ankle fracture effectively ended his work career.

He appealed for a military pension from the U.S. Government because of the growing problems of his injuries. He was refused and the family was apparently forced to move into Ogdensburg's noisy industrial heart. Finally he was granted a pension of $12 per month.

Unable to work, he turned to writing the story of “a man who could sell his own children or who would uphold a system that enabled him to do so. The thought is a horror.” Sales of the book at 25 cents each helped support his childrens' education.

He closed the 40-page story with a plea to any surviving family members to get in touch with him at his Ogdensburg postal address.

He died of a heart attack in 1905 and was buried with military honours in Ogdensburg.

But 30 years later in Winchester, in a testimony to the resilience of the human spirit, Isaac Johnson was hard at work on a new limestone Methodist Church. The skilled stone mason had learned in a harsh world the importance of basic principles, from freedom to construction.

When he discovered that the north wall of the new building was a half-inch out of line, according to a story, he tore down the wall, which had reached the top of the windows. Then he started over again from the six-foot-wide foundation.

Perhaps Johnson or another mason was responsible for a unique feature. Over the windows on the south side are the figures of a sun, half-moon and star clearly visible in stone. The campaign to restore the former Methodist church, now Winchester United Church, has created challenges that some feel are too much to manage. But the history of the 130-year old limestone landmark and its predecessors is a story of struggle, division and tragedies as well as faith and happiness. They make the current campaign to raise $200,000 this year to restore the stately bell tower seem much more manageable.

Johnson carried a terrible truth in his heart as he worked on the church that summer - a project which would ultimately take five years to complete.

But he perfected the skills that would soon lead to a successful career building hospitals, churches, bridges and town halls in Northern New York State and Eastern Ontario. He probably thought often of that day staked to the post under the hot Kentucky sun. When he looked at his mother in the auction ring, “it seemed as if my mother's heart would break”, he recalled in a 1901 memoir. She knew all too well what was happening and who was responsible for the breakup of the family. He pleaded with his new owner to go to his mother. "Come along with me,” he snapped. "I will train you without your mother's help." The final shock was the sale of his youngest brother, two-year-old Eddie, who was taken from his mother when the bids for the two together were too low. He wrote "in a very short time, our happy family was scattered without even the privilege of saying 'Goodbye' to each other, and never again to be seen."He published the memoir "Slavery Days in Old Kentucky" in a bid to find his family. He also wanted to smash the romantic myths about the Confederate South and slavery. "Any system of human slavery is always degrading both to the master and slave."His efforts to find his family failed. But he discovered that the person who had ordered the sale of the family was his father, Richard Yeager, a white tobacco farmer.He had inherited Jane Johnson from his slave-trader father. She was kidnapped in 1840 from Madagascar, an island off the coast of Africa. The couple appeared to live happily as husband and wife raising a family and running the most prosperous farm in the area. But the social pressures from a racist community scandalized by a white man living with a slave woman became unbearable.

He sold the farm and disappeared. The family that was still expecting his return two months later instead was met by a sheriff ordered to sell the family to the highest bidders. Jane Johnson sold for $1,100 while Eddie sold for $200. In total the family went for $3,300.

Isaac was treated harshly by his new owners, working 18-hour days, just two meals a day and frequent whippings. Twice he tried to escape.

One warned Isaac that if he disobeyed, "my duty is to kill you just as I tell you to kill the mule if he doesn't do what is right. There is no more harm in me killing you than than there is in you killing the mule.” The same slave-owner caught his wife teaching slaves lessons from the Bible. “If you teach them to pray and read they may think they are human beings and we will not be able to keep them as slaves.”

The lessons ended and many slaves forgot what they learned “except the Lord's Prayer, so simple and yet so full of meaning and comfort.”

Isaac was forced to watch a fellow slave, Bob, whipped, tortured with hot coals and slowly killed over five days as an example for leading a runaway group. Bob, a formerly free Canadian steamboat engineer kidnapped in New Orleans, had told Isaac of the freedom that beckoned in Canada.

Much later Isaac would meet the sadistic slave-owner - now paralyzed and confined to his bed. "The Lord has answered my prayers and allowed me to see him punished."

As for his father, he was "repulsive" because he could sell his own children and support a system that allowed that to happen.

Isaac finally broke free when the Union Army marched through Kentucky in 1863. When the slave-owner came looking for Isaac, the commanding officer gave his master 15 minutes to clear out. Captain Larkin Smith gave Isaac a job as a cook and revolver and 20 bullets. Isaac relished the first freedoms in his life - to work for pay and to bear a weapon to protect himself. Smith and his regiment returned to their home state of Michigan. From Detroit, Isaac looked across the river to Windsor. “I was going to Canada because then I would be a free man.” But it was 1864 and there was some unfinished business. He enlisted in a new black regiment of the Union Army and was wounded in action in battles in South Carolina.

He lost a finger on his right hand and took three bullets in his left arm which were never removed and caused him trouble as the years advanced.

After the war was over, he spent two years searching for his family in Kentucky. He then worked as a sailor on the Great Lakes and finally stopped at Morrisburg. Later he would recall “I never set my feet upon Canadian soil, even to this day, without a feeling of love and respect for its people of Canada, to me a Canaan.”

He lived in Winchester for about eight years, winning respect for his skills as a stone and lime mason. He married Theodocia Allen on Dec. 28, 1875. She had been born in New York and at 20 was ten years his junior. From pictures it appears she was likely white. On the wedding document for the Morrisburg ceremony, he said he was a "lime mason." Both were Methodists. Gertrude, the first of seven children, was born in Winchester in 1876 and Susan followed five years later. They lived in a log house on the west side of Main Street across from the quarry on a farm that is still in the Baker family. It is about two kilometres south of the church.

Isaac's story was re-issued and updated with an introduction by the St. Lawrence County Historical Association in 1994. Their researchers discovered that Earl Baker, before his death, told researchers that “Mr. Johnson” was remembered in family stories for developing the quarry, building the family home (near a new Anglican Church) and other fine local stone buildings.

The quarry is now full of water and edged by trees. An adjacent property was once a municipal dump.

Isaac also likely worked in lime and quarry operation owned by the Summers family just to the west of the current intersection of County Road 43 and Belanger Road.

The determined young man with a fierce mutton-chop beard and strong eyes stood five feet, eight inches high and his skin was light. One master had derisively described him as a “pumpkin seed nigger from the mountains.” But the new post-war world was booming and opportunities for expert builders were many regardless of race. In the winter months, he worked with wood. He carved a small wood chair for a family friend in 1873. Now in a Waddington museum, it features African patterns and markings.

In 1884, while work continued on the new Winchester Church, he won a contract in Waddington, opposite Morrisburg, for a handsome new town hall and for a stone bridge to the south. He also built a Catholic Church in the area.

He moved to Waddington and later to faster-growing Ogdensburg as new opportunities opened to build a new state mental hospital.

He continued to work on both sides of the border. In 1897 he was injured in a fall from a derrick at a Cornwall quarry. The serious ankle fracture effectively ended his work career.

He appealed for a military pension from the U.S. Government because of the growing problems of his injuries. He was refused and the family was apparently forced to move into Ogdensburg's noisy industrial heart. Finally he was granted a pension of $12 per month.

Unable to work, he turned to writing the story of “a man who could sell his own children or who would uphold a system that enabled him to do so. The thought is a horror.” Sales of the book at 25 cents each helped support his childrens' education.

He closed the 40-page story with a plea to any surviving family members to get in touch with him at his Ogdensburg postal address.

He died of a heart attack in 1905 and was buried with military honours in Ogdensburg.

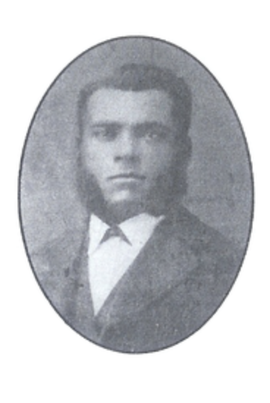

Isaac Johnson around the time of the construction of Winchester United Church

Isaac Johnson around the time of the construction of Winchester United Church

The earliest members of the future Winchester United Church faced challenges in the tiny pioneer community of a few hundred people. For years several denominations met in a log school house near the current Baptist Church on Main Street starting in 1832. They travelled to the tiny village then known as Bates Corners by horse-drawn sleighs over deeply-rutted winter roads or by carriage and wagon. Many swampy roads through the deep bush were impassable for months on end.

Life could be harsh and short and medical treatment could be far away. A baby born in 1850 could expect to live to 40 on average. If they survived the challenges of the first ten years, they had a good chance of making it to 60.

The church they built became of a sanctuary in hard times and a rallying point when international troubles like war came. The members supported the poor in their midst and the broader community. Seven church members died serving Canada in world wars. Others would be elected to serve the region as MPs, MPPs and cabinet ministers.

The church was a rallying force against social problems particularly rampant alcoholism Winchester went dry by a local vote 20 years before Prohibition and stayed dry long after _ much to the delight of bootleggers.

The first permanent stone church building was built on the south side of Main St. just west of Mill Street in 1857. It was a Methodist Church, an evangelical strain of Christianity which found favour with pioneers. Like the original school property, it housed several other denominations all seeking to convert souls with marathon camp revival meetings.

Sunday was a major all-day event with services at 10.30 and 7.30 and Sunday school in the afternoon.

Church membership grew but there were divisions to bridge. Even with Methodism, there were several strands each with its own vigorous supporters.

The divisions hardened when it came time to build the first permanent church for the Methodist community.

The congregation was badly split between picking a site on St. Lawrence Street south of Winchester Public School or a site on Main street east of the current Wesleyan church.

The battle see-sawed for years during the 1850s and building materials were shipped back and forth. Nature stepped in with a big wind storm which flattened the partially-built church, scattered building materials and put everything on hold.

The final plan to build the current church coincided with the consolidation of several Methodist and related churches across Canada. Finally Winchester was ready to build in 1881 with a princely budget of $10,000 and an ambitious fund-raising campaign.

"We can commend the brethren for their liberality to so noble a purpose," a church newspaper reported. "There are many that are subscribing a thousand a piece and others well up in the hundreds."

The $10,000 they raised is the equivalent of $239,000 in today's dollars.

With the purchase of the St. Lawrence street lot in the spring of 1881, church leaders hitched a double buggy with fine horses to study churches in Ottawa. There were disagreements so they gave several sketches to J.P. Johnson of Ogdensburg to draw up the final plans.

The unique and beautiful Sunday School with tiers of rooms rising to a multi-section roof was completed and opened for use in the first year. A drive shed was built to shelter horses and buggies in what is now a parking lot.

Construction was hands-on and it was difficult. John Benjamin Baker, likely Isaac Johnson's employer and landlord, died of internal injuries suffered lifting a heavy stone window sill from a wagon at the site.

Baker was a leading member of the church and the limestone came from a quarry on his farm. Together with his six sons he worked on the project and supplied the stone and lime for cement for just $1,000.

The stone was cut by hand. First holes were drilled, two iron rods inserted and wooden wedges driven between to split the rock. The lime used to create mortar was just as tough and dangerous to make.

Highly unstable blasting powder reduced the stone to manageable pieces and dust. It was heated in a kiln for three days and nights to create the lime.

The building was built with materials from the region: window frames from Morewood and the pulpit and communion table from the M.F. Beach plant in Winchester. It stood up well. The original windows lasted until 1951 and the original slate roof until 1977. Four wood-burning furnaces heated building for many years.

The building was lit by kerosene lamps. A caretaker was responsible for lighting each lamp with a long taper. Later carbide gas was piped to each fixture. The first electric fixtures arrived only about 1926.

The church has gone through many changes in the 130 years since construction was completed. Church members and the wide community have banded together repeatedly over the years to upgrade and improve the structure.

The acoustics in the main church are excellent, supporting music from church services to a recent country music festival and popular Broadway music show.

Ed Lawrence, the famed CBC gardening expert, praised the unique Sunday school structure with its multi-sectioned roof and fine woodwork in a popular presentation to a large group of gardeners.

Winchester United, like most traditional churches, faces new challenges in an increasingly secular society.

But the experience of the original pioneers and the determination of today's members shows that a new path can be found to make the Old Limestone Lady on St. Lawrence Street a valued part of the community for generations to come.

Life could be harsh and short and medical treatment could be far away. A baby born in 1850 could expect to live to 40 on average. If they survived the challenges of the first ten years, they had a good chance of making it to 60.

The church they built became of a sanctuary in hard times and a rallying point when international troubles like war came. The members supported the poor in their midst and the broader community. Seven church members died serving Canada in world wars. Others would be elected to serve the region as MPs, MPPs and cabinet ministers.

The church was a rallying force against social problems particularly rampant alcoholism Winchester went dry by a local vote 20 years before Prohibition and stayed dry long after _ much to the delight of bootleggers.

The first permanent stone church building was built on the south side of Main St. just west of Mill Street in 1857. It was a Methodist Church, an evangelical strain of Christianity which found favour with pioneers. Like the original school property, it housed several other denominations all seeking to convert souls with marathon camp revival meetings.

Sunday was a major all-day event with services at 10.30 and 7.30 and Sunday school in the afternoon.

Church membership grew but there were divisions to bridge. Even with Methodism, there were several strands each with its own vigorous supporters.

The divisions hardened when it came time to build the first permanent church for the Methodist community.

The congregation was badly split between picking a site on St. Lawrence Street south of Winchester Public School or a site on Main street east of the current Wesleyan church.

The battle see-sawed for years during the 1850s and building materials were shipped back and forth. Nature stepped in with a big wind storm which flattened the partially-built church, scattered building materials and put everything on hold.

The final plan to build the current church coincided with the consolidation of several Methodist and related churches across Canada. Finally Winchester was ready to build in 1881 with a princely budget of $10,000 and an ambitious fund-raising campaign.

"We can commend the brethren for their liberality to so noble a purpose," a church newspaper reported. "There are many that are subscribing a thousand a piece and others well up in the hundreds."

The $10,000 they raised is the equivalent of $239,000 in today's dollars.

With the purchase of the St. Lawrence street lot in the spring of 1881, church leaders hitched a double buggy with fine horses to study churches in Ottawa. There were disagreements so they gave several sketches to J.P. Johnson of Ogdensburg to draw up the final plans.

The unique and beautiful Sunday School with tiers of rooms rising to a multi-section roof was completed and opened for use in the first year. A drive shed was built to shelter horses and buggies in what is now a parking lot.

Construction was hands-on and it was difficult. John Benjamin Baker, likely Isaac Johnson's employer and landlord, died of internal injuries suffered lifting a heavy stone window sill from a wagon at the site.

Baker was a leading member of the church and the limestone came from a quarry on his farm. Together with his six sons he worked on the project and supplied the stone and lime for cement for just $1,000.

The stone was cut by hand. First holes were drilled, two iron rods inserted and wooden wedges driven between to split the rock. The lime used to create mortar was just as tough and dangerous to make.

Highly unstable blasting powder reduced the stone to manageable pieces and dust. It was heated in a kiln for three days and nights to create the lime.

The building was built with materials from the region: window frames from Morewood and the pulpit and communion table from the M.F. Beach plant in Winchester. It stood up well. The original windows lasted until 1951 and the original slate roof until 1977. Four wood-burning furnaces heated building for many years.

The building was lit by kerosene lamps. A caretaker was responsible for lighting each lamp with a long taper. Later carbide gas was piped to each fixture. The first electric fixtures arrived only about 1926.

The church has gone through many changes in the 130 years since construction was completed. Church members and the wide community have banded together repeatedly over the years to upgrade and improve the structure.

The acoustics in the main church are excellent, supporting music from church services to a recent country music festival and popular Broadway music show.

Ed Lawrence, the famed CBC gardening expert, praised the unique Sunday school structure with its multi-sectioned roof and fine woodwork in a popular presentation to a large group of gardeners.

Winchester United, like most traditional churches, faces new challenges in an increasingly secular society.

But the experience of the original pioneers and the determination of today's members shows that a new path can be found to make the Old Limestone Lady on St. Lawrence Street a valued part of the community for generations to come.